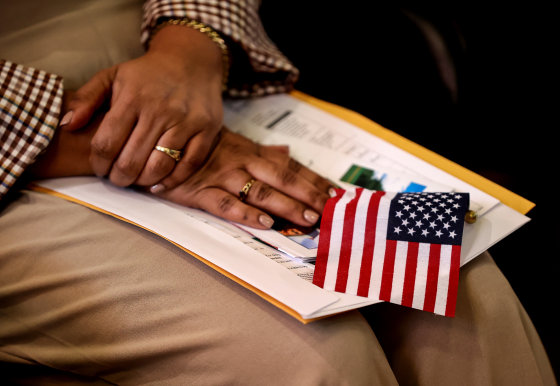

How Trump’s birthright citizenship order could affect children of legal visa-holders

Legal experts warn that those whose parents are on work and student visas won’t be exempt from the implications of the new order.

As immigrants across the U.S. contend with President Donald Trump’s executive order on birthright citizenship, legal experts are sounding the alarm on what it will mean for visa-holding families.

The order, issued Monday on Trump’s first day back in office, declares that not all children born in the U.S. are automatically granted U.S. citizenship. Specifically, for children whose parents are either undocumented or on temporary visas — for work, travel or school — citizenship will not be a given.

For some Asians, who dominate high-skill work visas like the H1B and student visas like the F1, this prospect could be life-altering, experts say. If one parent is not a U.S. citizen or permanent resident at the time of the child’s birth, the order says, their child will not be a citizen.

Experts say that this is in direct violation of the Constitution and that the Supreme Court may not uphold it, but many immigrants are already afraid. Bethany Li, executive director of the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, says she sees Trump’s move as an attempt to exclude certain groups based on race.

Related:

Trump aims to end birthright citizenship, says American citizens with family here illegally may be deported

“This order doesn’t just target undocumented people,” Li said. “It targets people that come in through student visas. It targets people who have tourist visas. That order, ultimately, is about who Trump considers American.”

Twenty-two states and several other entities have filed lawsuits against the Trump administration contesting the order, which experts say violates the 14th Amendment, which says, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

The Trump administration didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Trump’s order argues that the clause “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” disqualifies children of these groups.

Experts say that beyond being unconstitutional, the order has the potential to create some bureaucratic headaches, as certain countries don’t automatically give citizenship to those not born in the country — even for children born to parents who are citizens — meaning some kids might be temporarily stateless.

Related:

24 Democratic states and cities sue over Trump’s bid to end birthright citizenship

“There could be a whole generation of stateless children who are not citizens in the United States, but they’re not citizens elsewhere either,” said Aarti Kohli, executive director of the Asian Law Caucus, one of the organizations that is suing the Trump administration over the order.

For families seeking asylum after being facing political persecution in another country, the situation might be even more complicated.

“We have asylees from Afghanistan, from China. Our plaintiffs are from Indonesia and they’re asylees,” Kohli said. “It’s very unlikely that they will be able to get travel documents or identity documents from the countries that they’re fleeing for their child.”

Li sees the birthright citizenship order as a distraction, she said, as the 14th Amendment is very clear. She doesn’t believe it will survive in court, but she thinks it could affect how desirable the U.S. looks to would-be immigrants from all over the world.

Related:

Trump signs order ending birthright citizenship for children of illegal immigrants

“This executive order is aimed at stopping Latino and Asian immigrants from coming into this country and building a life here, which is fundamentally opposed to the values of the United States,” Li said.

It also has the potential to resurface a climate of violence and scrutiny toward immigrant groups, Kohli said. She referred to the establishment of birthright citizenship in 1898, after a Chinese American, Wong Kim Ark, challenged the Chinese Exclusion Act before the Supreme Court.

“We had lynching of Chinese workers,” she said. “The atmosphere was incredibly racist, and still, our community fought and challenged this order.”

Li and Kohli said they worry that Trump’s first days in office are indicative of what’s to come for immigrants in the U.S.

“This speaks to sort of a larger policy orientation in the Trump administration, which is a real tightening of our immigration system, limiting access to visas,” Kohli said.

Li says both legal and undocumented Asian Americans, growing in number each year, should brace themselves for the next stage.

“I think there’s going to be so many other fights to be had,” she said.

________

NBC News