Judge Shortens Sentence for Convicted Murderer Turned Prison Mentor

A Hartford Superior Court Judge granted a sentence modification on Friday to Clyde Meikle, a man serving a 50-year prison sentence for killing his cousin in 1994.

“The Clyde Meikle of 1994 was a different person than the Clyde Meikle that stands before the court today,” Judge David Gold said before granting Meikle’s sentence modification, cutting his sentence from 50 years to 28.

Meikle killed his cousin Clifford Walker 26 years ago by shooting him in the stomach during a dispute over a parking space at his family’s house on Enfield Street in Hartford’s North End. Meikle, who long suffered from substance abuse and unresolved trauma at the time of the shooting, was sentenced to 50 years in prison in 1998. He has served 26 years so far, during which he has earned a GED and the credits for a college degree and become one of the founding mentors of the T.R.U.E. Unit, which pairs older incarcerated people with younger ones, to help keep them out of the prison system.

“Mr. Meikle has been confined within the walls of a prison for his 20s, his 30s and his 40s, the entirety of the adult life he has thus far experienced,” Gold said. “In light of the lengthy period of incarceration he has already served, the question now before the court is not whether Mr. Meikle’s violent past should cause him to lose the enjoyment of most of his adult life. It already has. Rather, the question is whether it should require him to lose the enjoyment of the rest of his life, whatever that period may be.”

Outlining the considerations he had to consider in making his decision, Gold said the case ultimately boiled down to weighing Meikle’s rehabilitation efforts against whether the 49-year-old’s release would pose any threat to public safety, whether Meikle has accepted responsibility for his actions and the effect on the Walker family, which Gold said has “had to pick up the pieces and hold them together in the aftermath of Mr. Meikle’s actions.”

‘Frivolous claims’

But Gold castigated Meikle for filing a litany of lawsuits over the years challenging his incarceration. Gold said Meikle filed legal motions blaming various lawyers for his getting locked up, claimed he should be awarded $13 million and alleged his prosecutor and Hartford police had lied at his trial.

“Since Mr. Meikle was convicted of murder, he has used, and in the view of some abused, the legal system to wage what has been a relentless attack against the fairness of the process that resulted in his conviction,” Gold said. The “wild and frivolous claims” accused “everyone else in the system of bearing responsibility for his imprisonment, except for himself,” Gold said.

Gold said Meikle “has every right to pursue all avenues of legal redress that are available to him, yet a person’s endless pursuit of frivolous claims in one court after another does tend to suggest that the person either does not, cannot or will not accept the reality of what has happened.”

Nonetheless, the judge granted Meikle’s petition, which had been supported not only by the state’s attorney who prosecuted him 26 years ago but former Department of Correction Commissioner Scott Semple and current Commissioner of the Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection James Rovella, who arrested Meikle in 1994 when he was a Hartford detective.

For the court to require Mr. Meikle to serve out the remainder of his sentence simply to fulfill the terms of the original judgment would not contribute in any meaningful way toward making him a better person when he is released.”

— Judge David Gold

“Mr. Meikle’s is the rare, if not unique, case in which the police detective who arrested him, the state’s attorney who prosecuted him and the state Commissioner into whose custody he was placed upon conviction, all speak with one voice in urging the court to grant the motion to modify and to reduce the presence sentence,” said Gold.

“Under such circumstances, for the court to require Mr. Meikle to serve out the remainder of his sentence simply to fulfill the terms of the original judgment would not contribute in any meaningful way toward making him a better person when he is released,” Gold said. “But it would only serve to make them an older one.”

Of particular importance, Gold said, was his decision’s impact on other people still in the prison system. To deny Meikle relief, Gold explained, would ignore the value of Meikle’s achievements and could serve as a disincentive for other incarcerated people who, in the hope of one day earning sentence reduction, might follow Meikle’s lead and seek to better themselves and others.

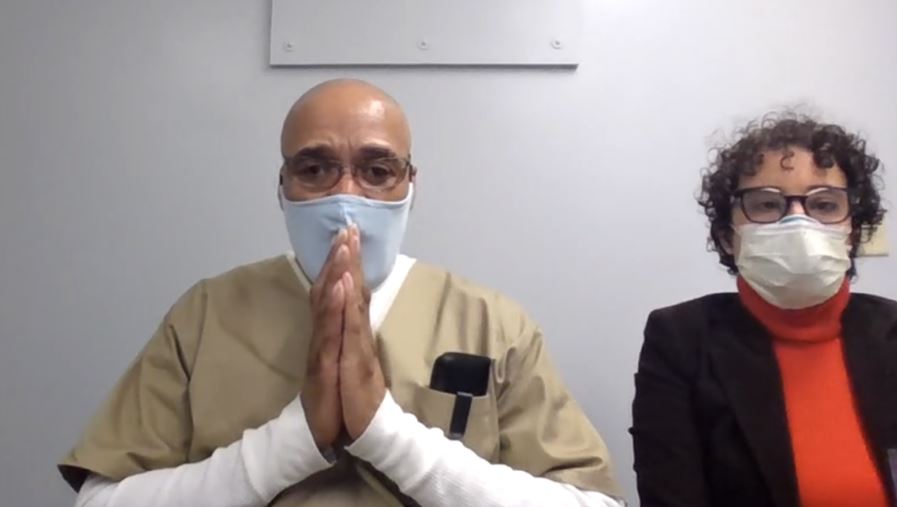

Meikle appeared to be praying silently as Gold spent a half-hour explaining his reasoning behind his ruling before revealing that he would cut his sentence to 28 years. His attorney, Miriam Gohara, a clinical associate professor of law at Yale Law School, placed her hand on his shoulder as Gold broke the news that Meikle would be going home, some day.

At least a half-dozen members of the Walker family, meanwhile, gathered together for the Friday morning hearing. Gold addressed them directly after announcing his ruling.

“I realized that these rationales and explanations are not likely to mean much to you. From your viewpoint, what I have done has just allowed the man who killed your loved one to escape the service of his full punishment,” Gold said, praising them for being the “only voices against the chorus” of Meikle’s many supporters in a Dec. 18 hearing on his sentence modification petition.

“To the Walker family, please do not interpret my reduction of Mr. Meikle’s sentence as meaning that Clifford’s life was somehow worth less. His life was priceless. And there is no prison sentence, regardless of its length, that can express the magnitude of your loss,” Gold said. “In my opinion, the strength that each of you showed during the hearing last month, and the strength that each of you has had to maintain since Nov. 1, 1994, is something far more worthy of praise and admiration than anything that Mr. Meikle has done, or will ever do in the future.”

At the end of the hearing, Gold told Meikle there were around 800 people in Connecticut prisons right now who are serving long sentences for murder.

“I suspect every single one of them would give everything to have even a fraction of the support that you do,” Gold said. “But yours is the case that has become the feel-good, almost inspirational story that so many have flocked to.”

The judge warned Meikle of the hard road ahead. Despite having much support from members of his community, Meikle will face struggles in his reentry, after having been in prison for 26 years.

“You’ve become accustomed to being looked up to by many in prison, but there’s a risk that you’re going to be looked down upon by many outside of it,” Gold said. “It’s nice being called extraordinary. It’s not so nice being called an ex-con.”

The Department of Correction begins screening incarcerated people for discharge to a halfway house 18 months before the end of their sentence, said Karen Martucci, the agency’s director of external affairs. In Meikle’s case, that would be sometime in the summer.

He will not be eligible for parole, per state law at the time of his sentencing.

Martucci said the DOC considers each inmate’s sentence, the transcripts from their court hearings, their conduct while incarcerated and victim impact in its decisions on discretionary releases. Those sent to halfway houses are supervised by parole officers, she added.

A vacancy in prison mentorship

There are 16 mentors on the T.R.U.E. Unit. Meikle’s eventual discharge will create a vacancy, perhaps an unprecedented one.

“Our mentors are lifers, so I’m not sure if there’s been any replacements until now,” said Martucci.

When the mentees leave the unit, they are replaced by other young incarcerated people, Martucci said. Meikle has been an “active mentor in that unit, so I can see where there’d be a hole upon his release,” Martucci said, explaining that replacing him will be the subject of future conversations between Cheshire Correctional Institution’s warden and other DOC officials.

Meikle’s case was watched closely by current and former officials, including those who helped start the T.R.U.E. Unit. Among those is Michael P. Lawlor, former undersecretary for criminal justice policy and planning for Gov. Dannel P. Malloy.

“People I think are coming to realize that the sentences imposed in this country are off the charts compared to many other place in the world,” Lawlor said, noting that Meikle’s 50-year sentence was “unheard of in the rest of the world, in almost any country where we would want to associate ourselves with.”

A close observer of criminal justice trends and data across the state and country, Lawlor said Connecticut’s prison population is changing; younger people now make up a smaller percentage of the incarcerated population, but the number of people over age 60 is growing.

“I would imagine most of them committed crimes 20 years ago and are still serving those sentences, and they’re not getting out,” Lawlor said.

He suggested the legislature follow the lead of places like Washington, D.C., and pass bills that make people eligible for parole who are locked up for violent crimes they committed before the age of 25.

“You have quite a few people who have committed crimes when they were very young, really serious crimes, and who were sentenced to 40, 50, 60 years without the possibility of parole. And now, 25 years later, some of them, at least, are different people,” Lawlor said. “This is something that’s new, and now public policy has to respond to it.”