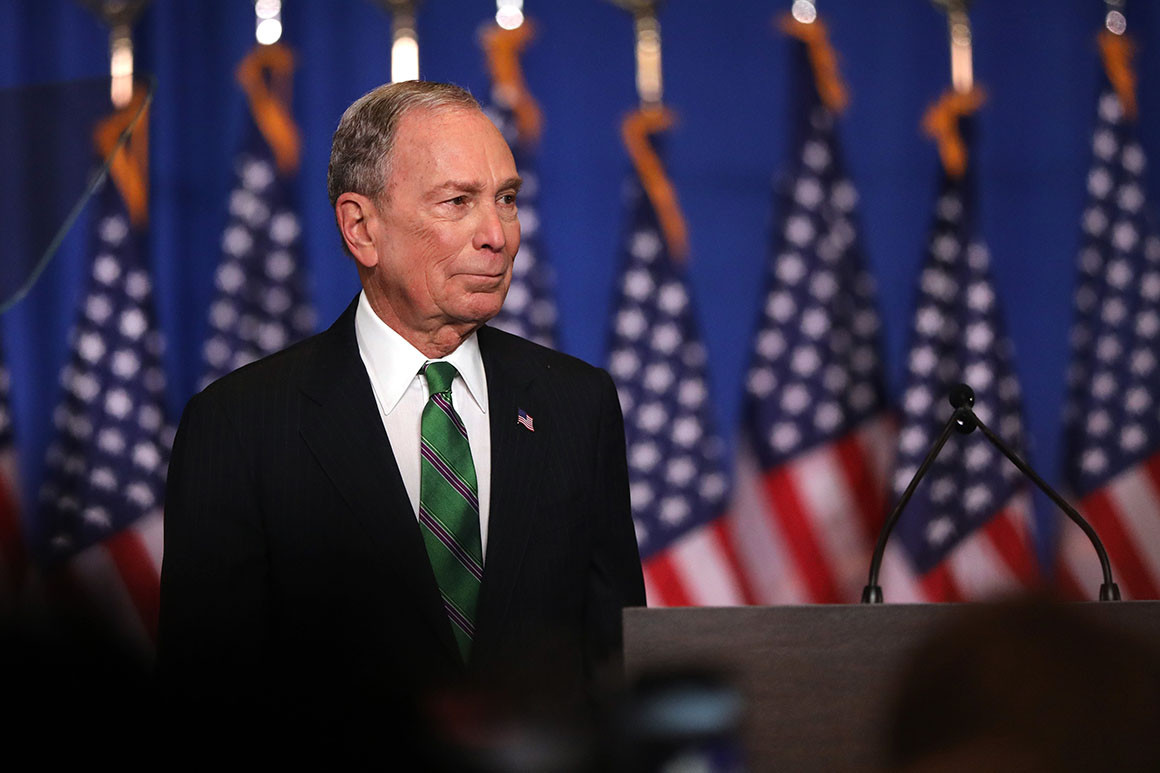

Mike Bloomberg Sued in Class-Action By Campaign Staff

Former campaign workers for Mike Bloomberg are suing the billionaire former presidential candidate for fraud, alleging in a nationwide class action lawsuit that as many as 2,000 employees were promised to be paid through the general election before he laid them off.

Plaintiffs in the class action include two organizers who halted the interview process for other jobs to join the Bloomberg campaign, and another former organizer who postponed law school to work on Bloomberg’s 2020 effort.

The filing comes on the same day as another class action brought by a former Bloomberg field organizer that similarly argues the employees were tricked into taking jobs they were told would continue for a year.

The lawsuit by the three former workers in Georgia, Utah and Washington state, also filed in federal court in New York City, contends that the field organizers were fraudulently induced to accept jobs with the Bloomberg campaign based on the promise of guaranteed salaries through November. The ex-field staffers who filed the suit, Alexis Sklair, Nathaniel Brown, and Sterling Rettke, are represented by Peter Romer-Friedman of Gupta Wessler PLLC, and Ilann M. Maazel and David Berman of Emery Celli Brinckerhoff & Abady LLP.

Bloomberg on Friday purged all of those workers in six battleground states and guaranteed they would be paid only through the first week of April, with their benefits expiring at the end of that month. The first big round of layoffs across the rest of the country happened earlier this month, with their pay lasting through March 31.

Bloomberg hiring materials described as coming from headquarters promised work with “Team Bloomberg” through November, regardless of whether he became the Democratic nominee, provided that the aides working across the country were willing to relocate. Bloomberg’s team reiterated their plans to follow through — even if only in spirit — after the initial round of layoffs, when top campaign advisers indicated in emails and staff conference calls that they would be given priority on a planned Bloomberg super PAC.

Instead, Bloomberg announced Friday that he had decided to transfer $18 million of his own money to the Democratic National Committee to help presumptive nominee Joe Biden. The campaign invited former field organizers to apply for jobs with the party through its “competitive process,” with no guarantee of a job.

“Thousands of people relied on that promise. They moved to other cities. They gave up school, jobs, and job opportunities. They uprooted their lives,” the lawsuit states. “But the promise was false. After Bloomberg lost the Democratic nomination, his campaign unceremoniously dumped thousands of staffers, leaving them with no employment, no income, and no health insurance.

“And, worse still, the Bloomberg campaign did this during the worst global pandemic since 1918, in the face of a looming economic crisis. Now thousands of people who relied on the Bloomberg campaign’s promise are left to fend for themselves.”

Bloomberg aides were also told that the field offices in battleground states would remain open.

A Bloomberg spokesperson issued a statement Monday saying the campaign paid its staff wages and benefits that were “much more generous” than any other campaign this year. They said staff worked 39 days on average, but they were also given several weeks of severance and healthcare through March.

“Given the current crisis, a fund is being created to ensure that all staff receive health care through April, which no other campaign has done,” the spokesperson said. “And many field staff will go on to work for the DNC in battleground states, in part because the campaign made the largest monetary transfer to the DNC from a presidential campaign in history to support the DNC’s organizing efforts.”

Attorney for one of the group of litigants said in a statement that while “our clients would like to speak publicly about their experiences, they are potentially subject to a confidentiality and non-disparagement agreement with Mike Bloomberg 2020. We respectfully request that the Bloomberg campaign release our clients and the other field staffers from that agreement, even though it may not be enforceable.”

Attorneys not working on the cases said such class action lawsuits are often combined.

Bloomberg field organizers were among the highest compensated in the election cycle, and enjoyed generous health benefits, in addition to $5,000 for relocation costs.

While all of the field organizers are believed to have signed at-will contracts with the campaign, they argue in the lawsuit that they can bring these claims based on evidence that they were induced to sign on because of the longevity promises made to them.

The promise of sustained pay months after a campaign ends is exceedingly rare in politics. But in more than a dozen interviews with POLITICO, the former aides said it was key to their decision to join. Bloomberg quickly amassed a staff of thousands after launching in November, then ended his campaign after a feeble showing on Super Tuesday.

Since news of their dismissal, scores of former Bloomberg staffers have been organizing online in preparation for taking legal action. They’ve established several chat and email groups to share their experiences, with many expressing deep frustrations about losing their pay and health care benefits in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

Aside from the action filed Monday, there are believed to be other claims coming from other groups of ex-staffers.

The lawsuit states that Sklair relocated from Charleston, S.C. to Savannah, Ga., to work as a field organizer for Bloomberg. Before joining the Bloomberg campaign, she was an organizer for Cory Booker’s presidential campaign.

At the time that Sklair accepted the job with Bloomberg, the lawsuit states, she had just been offered a position on a state Senate campaign in South Carolina that would have likely lasted throughout the general election. After taking the job with Bloomberg, she declined to move forward.

Brown worked as an organizer for Kamala Harris’ presidential campaign and moved from Las Vegas to Salt Lake City, Utah to work for Bloomberg in January. He said he dropped out of advanced stages of the hiring process for a job as an organizer with the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

Rettke postponed applying for law school to work on Bloomberg’s bid.